Mixed-use development is coming to NZ cities, here’s One Small Trick to take it further

Allowing neighbours to sell their planning rights to incoming developments will make a good policy even better

The New Zealand government wants cities to allow more mixed-use development in areas that have previously been zoned for housing only, which is great – homes and shops side-by-side make for thriving, lively neighbourhoods. We should allow incoming developments to negotiate a price with neighbours to waive restrictive planning rules too, to make more types of mixed-use development even easier and in more locations.

Mixed-use is coming to our cities

Minister for Housing Chris Bishop has recently announced a reform package intended to free up more land for development: Going for Housing Growth. One of the actions is to enable mixed-use development in our largest cities, via new national direction:

Tier 1 and 2 councils will be required to enable “a baseline level of small-scale mixed-use (such as dairies and cafes) across their urban areas”

Tier 1 councils will also be required to enable “a specified set of small-to-mid- scale activities (such as restaurants, retail, metro-style supermarkets and offices) in areas subject to the NPS-UD’s intensification requirements [ie, walkable catchments from rapid transit spots, city centres and commercial centres]”

Tier 1 councils are our biggest cities (Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, Hamilton, Tauranga) while Tier 2 councils are our secondary cities.1

This is great policy – this will help bring commercial rents down, make the suburbs more vibrant, reduce the need for driving, and enable more competition and choice. Malcolm McCracken has a great post on how mixed-use zoning will let cities flourish, especially if paired with complimentary policies like managing parking and beautifying local centres.

We used to allow a lot more commercial shops mixed in with residential, which is what makes the older tramway suburbs in our cities feel so lively. But modern planning doctrine2 has since separated uses and designated hierarchies of centres, leaving residential areas feeling cold and boring while forcing nearly everyone to drive to main hubs for shopping and entertainment.

Enabling cafes and dairies is politically palatable – larger businesses are trickier

Bishop’s speech announcing the reforms talks about directing councils to enable the types of shops that people like having near them, like cafes and dairies, which tend to fit into existing communities with little disruption.

But as these are top-down directions for councils to either implement or interpret, the government can only go so far. Enabling large businesses and intense commercial uses in all areas is politically unpalatable. As we saw with the Medium Density Residential Standards (MDRS) backlash, residents in politically vocal suburbs balked at townhouses being allowed near them, which led to the entire policy being scrapped. There is a political limit to broad, top-down policies – they have to cater for any situation that would generate significant opposition, to ensure the entire package retains support.

We need more commercial (and industrial) zoned land, but there are real negative externalities

As our cities densify, we need more small-scale shops, offices, and cafes in the suburbs. But we also need more large-scale retail and industrial. The Commerce Commission found that a lack of suitably-zoned sites is a big constraint on competition for large-scale retail like supermarkets, petrol stations and building materials suppliers. That makes it hard for competitors to enter an area or for an entirely new entrant to break into the country (like a third supermarket chain to break the duopoly).

Anecdotally, areas like Auckland’s North Shore are ‘running out’ of commercial and industrial zoned land, even though the council thought it had zoned enough for the next few decades. Companies like Woolworths continue to run old supermarkets literally across the road from new ones,3 an apparent strategy to keep prime land out of the hands of competitors that only works if there are very few viable sites left in a city.

But there are real negative externalities that come with new commercial spaces of all varieties, and some people will understandably be opposed to a large store or petrol station opening next door.

Obviously, there are widespread benefits that flow from new commercial developments, but the costs are concentrated on neighbours. At the moment, our planning system protects nearby properties from new, negative effects. But there is no mechanism for these neighbours to decide to waive those protections (for a price!). We should let them make this trade-off if they want to.

The inflexibility of the current planning rules is why you tend to see a lot of large-scale retail either placed at the edge of town where there is no one (yet) for it to negatively effect (for example, Costco in Westgate, Auckland), or you see large shops replace old industrial sites, or petrol stations replace old mechanics, as the externalities of these sites are already an accepted part of the urban fabric.

A recent paper4 argues that local residents tend to engage in NIMBYism and oppose new development because they are incapable of being compensated for the concentrated costs they would incur, despite new projects in high-demand areas generating huge surplus value (which could be used for a generous pay-out to neighbours!).

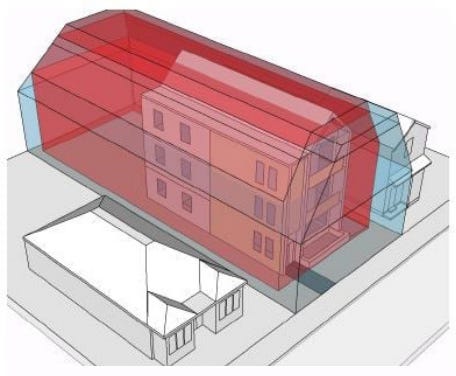

We should allow neighbours to sell their planning rights to incoming developments

Say an incoming development is on a site that borders two neighbouring properties. It could be hugely successful, but the current planning rules that protect neighbours – like setbacks and height in relation to boundary rules – will make the development infeasible. That development should be able to negotiate a price with the neighbours to waive their planning rights so the development can proceed. Everyone wins – the development can be a success for the wider area, and the neighbours get a big payout to compensate for the new disruption. That payout could fund double glazing and frosting to block noise, plus some extra to do some other nice renovations or pay off the mortgage. Some may even use a payout to help them sell and move somewhere else entirely.

An amendment to the Resource Management Act in 20175 deemed ‘boundary activities’ as permitted (no resource consent needed) if the affected neighbour provides their approval. This makes a lot of sense – these rules are for a neighbour’s benefit, so they should be able to waive them if they desire.

However, this rule is quite limited in a few ways. I suggest some changes:

Allow the waiver to be obtained for a price. Currently a neighbour can give their approval for free, only. In practice, this means the rule is only being applied to small rule infringements between neighbours who get on well. Few people would give approval for free, for the benefit of a commercial development.

Expand the definition of ‘boundary activity’. Currently it only applies to rules relating to the distance or dimension of a structure from a boundary. It should be expanded to include anything that affects a neighbouring property – shading, privacy, height, even things like opening hours and traffic access.

Allow reciprocal waivers. A neighbour waiving their rules should be able to (on top of a cash payout) negotiate reciprocal waivers benefitting their own property at the same time. This will avoid the issue that, when that neighbour wants to redevelop, new residents or commercial tenants refuse to negotiate or even object to their resource consent (i.e., ‘reverse sensitivity’ issues).

Permission should be attached to (‘run with’) the land’s title so an incoming development doesn’t waste time signing with the current occupiers only for a sale requiring a whole new negotiation process.

These changes would be in line with the Government’s stated intention to move to a planning system “based on property rights”. They apply a type of ‘Coasean bargaining’ theory; negotiations between private parties can arrive at an efficient outcome when property rights are well-defined and there are low transaction costs.

Currently planning rules manage effects via councillors and council officers making their own judgments on behalf of neighbours – currently the prevailing judgement seems to be, ‘everyone would hate a café right next door, therefore it’s banned everywhere!’ Rights to object are just that – a right to have your voice heard (which is often a de facto veto power). But there is no corresponding power to say yes, and no mechanism to allow for side-payments to compensate for new externalities.

A true property right doesn’t just give you the power to exclude (say ‘no’) but also the power trade your rights away for money (say ‘yes’).

Will there be any uptake?

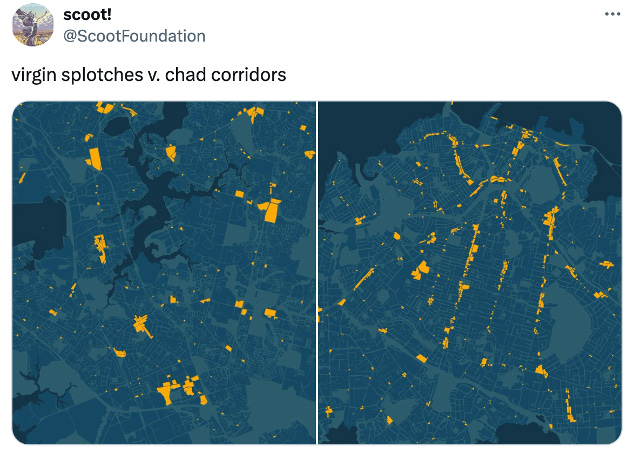

I view this kind of ‘bottom-up’ policy as a compliment to the ‘top-down’ policies that dictate to councils. My own view is that we should push up to the political limit of what is possible with top-down policies, to get a drastic one-off expansion of residential and commercial zoning. ‘Bottom-up’ style policies can then reach where directive policies can’t, and help create a more flexible planning system that is responsive to changing demand over time. Any scarcity of land that causes high rents will increase the incentive to use this waiver system. I expect this policy to be politically enduring too, as it’s a win-win for everyone involved.

There are still challenges to the use of a waiver system. Transaction costs still exist. There are holdout problems, where one neighbour may try ask for a very high price, or just refuse to engage at any price.6 And it wouldn’t solve land amalgamation, which remains an challenge for large-scale retail in areas with many small fragmented lots.

But there is no harm in trying. It’s a relatively simple change that doesn’t require plan changes from councils, and builds on an existing RMA amendment. It’s worth giving a go.

Whangārei, Rotorua, New Plymouth, Napier-Hastings, Palmerston North, Nelson Tasman, Queenstown, Dunedin.

Essentially from the Town and Country Planning Act 1977, and to a lesser extent, the TCPA 1953.

Famously in Napier, as seen in this Guy Williams video. See also Johnsonville, Upper Hutt and Manukau.

Foster and Warren (2022) “The NIMBY Problem” Journal of Theoretical Politics 34(1) at 145-172.

The usual resource consent and plan change processes are still available to rezone land.